Police and Black Men Project - Minneapolis

WELCOME

In the aftermath of local police-involved shootings, a group of Black Men and Minneapolis Police Officers came together to discuss the issue of distrust between Black men and the Police. The group began meeting in 2017.

Our mission: We are a group of Minneapolis Police Officers and Black community members building relationships of trust to promote community safety.

Learn more about the Police and Black Men Project by continuing down this page!

Origin Story and Developments

The project came out of a conversation between Bill Doherty, of the University of Minnesota’s Citizen Professional Center, and Guy Bowling, director of the FATHER Project in Minneapolis. Bill (a White man) and Guy (a Black man) had worked together on community projects for many years. Their conversation occurred in the summer of 2016 when the community was reeling from the death of Philando Castile after a traffic stop by a police officer in Falcon Heights, Minnesota. Guy said that he was reaching “outrage fatigue” and posed the question about whether Bill’s Families and Democracy model could be applied to the problems between Minneapolis police and Black men. This approach focuses on grass roots relationship building prior to action steps, rather than traditional top-down programming.

The basic idea that emerged was that a small group of police officers and Black men from the Minneapolis community would meet frequently over at least a year to develop relationships of trust and then decide on joint action steps.

Bill and Guy knew they could personally recruit the Black men from the community, but neither had ties to the Minneapolis Police Department. So Bill consulted with a well-connected friend who suggested starting by running the idea past Bob Kroll, head of the police union. Bill sent Lieutenant Kroll an email in January 2016 and immediately received a positive response and an invitation to meet Officer Dave O’Connor, a union leader and public engagement officer. That month Bill met over coffee with Dave and his partner, who were enthusiastic. Dave then discussed the idea with his colleagues and superiors, and got green lights. Finally, Bill contacted Police Chief Janee Harteau who met with him along with her Community Liaison Sherman Patterson. The Chief approved the idea with great interest, and entrusted Sherman Patterson with setting up a process of selecting the officers.

The initial group recruited consisted of five male officers (five White, one Black) and six Black men from the community. (One White officer subsequently dropped out and was replaced by another Black officer.) Officers were nominated by a group consisting of Deputy Chief Arradondo, Community Liaison Sherman Patterson, Officer Dave O’Connor and Bill Doherty (Bill had final screening authority). Once a group was nominated, we met with the Precinct Inspectors to get their buy in and willingness to approach the nominated officers. The Inspectors were uniformly positive about the project and then recruited their officers. The community members were nominated by Guy Bowling and Bill Doherty (one was nominated by Sherman Patterson), and were interviewed by Bill, Guy, and Sherman. We decided to alternate meetings between a police training facility and a community-located facility (UROC–the Urban Outreach and and Outreach/ Engagement Center of the University of Minnesota).

The group began biweekly meetings in January, 2017, with this goal: to forge connections between police officers and African American men that can lead to better partnerships for community safety and law enforcement. With Bill facilitating, we used a process of building relationships through personal storytelling, then opening up challenging topics, and deciding to create a common narrative to describe who we are, how we see the problem, what we envision for a safe community, and how we act together to bring about change. The group began its public action efforts in the fall of 2018. Our involvement in police training began in November 2019, with a training workshop for Cadets.

After the onset of the pandemic and the killing of George Floyd in May 2020, the group’s public activities went on hold. We had some of our most difficult and pained conversations (via Zoom) in the ensuing months, and we held together as a group. One of our police officers resigned and moved to a new police district, and another took a leave and later left the Minneapolis Police Department. In summer of 2021, we decided to return to in-person meetings and recommit ourselves to the work ahead.

In 2023 we added new officers and community members and decided to focus our work around trips to the Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama with officers and community members doing a deep dive into the history of slavery and Jim Crow, including the involvement of law enforcement in this history. We had our first trip in December–a powerful experience of learning and bonding. (The photo on the home page was taken in Montgomery.) We are planning to bring more groups to Montgomery and develop a community of officers and community members around this shared experience.

In 2024 we added three new officers and three new community members for our second trip to Montgomery, Alabama, this one for two days instead of one. We visited additional sites and had more time for processing the experience as well as bonding as an expanded group. Accompanying us were a journalist and documentarian from Minnesota Public Radio. We plan to use the trip and the documentary as a springboard get out our message in 2025.

Our way of working

This material is for people who want to take a deep dive into how we’ve done our work.

Our process involved going deep over time with a small group of officers and community members, without knowing at the start what action steps we would eventually take. We’ve been meeting every other week for two hours using the Families and Democracy Model developed by Bill Doherty and colleagues. We started meeting in January 2017.

Phase One: Relationship Building

We did months of relationship building through storytelling. We started with everyone’s stories of early experiences with police officers. We moved to our stories of early experiences with Black men and then with White men. Everyone had five minutes to tell their stories, followed by reflections from the rest of the group. These stories were often poignant and powerful, and they included both infuriating and uplifting stories about community members and police. We all talked about our fathers, again with sad stories and positive stories. We got to know each other as human beings. We had some conflict during this phase of our work, but mostly we focused on understanding one another. We were building trust for the next phase.

Phase Two: Moving into More Turbulent Waters

As we engaged more difficult topics, we used a structured process where everyone got a chance to talk and be heard, with no expectation that we would come to a consensus any time soon. Sometime we went around the group to get everyone’s voice in before more general conversation. Sometimes a community member and a police officer engaged each other in rapid-fire back and forth conversation, with the rest of group quiet and then reflecting later on what they heard, felt, and thought.

An important milestone came with how we processed the Jamar Clark police shooting that had led to weeks of demonstrations and an encampment outside the Fourth Police Precinct in the same neighborhood where our meetings occurred. Our conversations were highlighted by sometimes heated exchanges between a Black officer who had been responsible for maintain safety during the occupation and a Black community member who had been involved in the occupation (and who had led earlier protests about policing). The “heat” in these exchanges generated “light” as the two men came to better understand where each was coming from, and they found some common ground. Neither was a villain in the other’s story.

Phase Three: Processing New Events

The thing about meeting for a long time is that distressing new events are likely to occur. We dealt with two new police shootings of civilians, one of an unarmed White woman and one of an armed and fleeing Black man. Community members learned about the anguish that the officers felt about these shootings, and officers learned about how generations of mistrust of law enforcement left community members feeling mainly outraged but sometimes numb—and not focused (in the way the officers were) on the details of whether the shooting was legally justified. In our conversations, the officers came to show emotion in addition to focusing on the details of the incident, and community members became willing to talk about what had happened the officers’ perspectives as well as their own perspectives. Through it all, we kept returning to the same table, not giving up on one another or our mission. Sometimes there were tears and hot anger, but we kept coming back to the table.

Phase Four: A Brotherhood Forms

As the months went by, group members began to talk about their sense of friendship and even brotherhood. We were proud to have difficult conversations and stay in relationship. We recalled and laughed about some of our “greatest hits” arguments and teased the two members who has served as gladiators for their own side. When one of them missed a meeting, group members would ask who was going to step into their combatant role! The group began to tease Bill the facilitator about his tight control of the process, a control became less needed over time.

As the climate in the group became more open, the officers increasingly shared their experiences with the human tragedies and scary situations on the job. Some also recounted stories of being taunted and ridiculed on the streets because of how the public judged the actions of other officers after police shootings. A community offered this common perspective: “You’re being profiled.” One meeting focused on supporting an officer who had come upon a horrific crime scene and was having trouble sleeping. Another meeting focused on supporting a community member who was struggling to not give up hope for personal and community change.

As we talked about the larger context of policing and the Black community, we had a breakthrough realization about stereotyping: that Police and Black men are subject to the common, dehumanizing stereotypes in the larger culture. Both are seen as violent, dangerous, impulsive, educated, and having broken families. This realization led to a series of conversations about how Police and Black men are set up as scapegoats for broader societal problems. Crime is a byproduct of neighbors lacking in jobs, housing, and other resources blamed on the community members themselves. Police are then sent in to control situations they did not create and in communities that do not trust them. A sense began to emerge in our group that both sides have a common “enemy” and that they are pitted against each other in a way that dehumanizes both sides.’

Phase Five: Developing Our Narrative

After we knew we had formed something solid, we decided to develop a common narrative to describe what we believed about the sources of mistrust between Police and Black men, what we envisioned for a better future, and what we could do together. A key step was the decision to focus on the goal of community safety, not just better policing, because community safety is much bigger than policing. A safe community, we knew, was one that fosters healthy relationships—and these relationships require the basics of good jobs, safe housing, and access to quality education and health care.

We agreed that one of the community members in the group led us through a process he had learned in creating a common narrative. Some homogeneous groups develop their narrative statement in a few hours of workshop. Ours took months of bi-weekly meetings partly because we had other things to talk about but partly because we had to struggle to find language we could all agree on. We knew we had to all stand behind every idea and word in the narrative.

As we finished the narrative document we realized that we were breaking new ground in the public conversation about Police and the Black community. We decided that in order to make a public impact, we had to name and push back against two most current competing narratives and their solutions: the Just-Change-the-Police Narrative versus the Just-Be-More-Responsible. These ways to frame the solution put the Police and the community against each other, and neither approach alone leads to safer communities. We declared our narrative as Shared Partnership for Community Safety. Safe communities are good for community members and good places for Police to work and live. And that means that both the Police and the community have as stake in creating the social and structural conditions for safe communities: housing security, jobs, education, health care, and other factors. The housing issue grabbed us the most because one of our members was in the midst of housing insecurity and the officers talked about messy and dangerous domestic violence calls coming from fights over who was going to stay in a house or leave with no where to go. And the officers viscerally loathed having to move homeless people buildings where they were warm into the deep winter cold where they had no shelter.

Phase Six: Initiating Action Steps

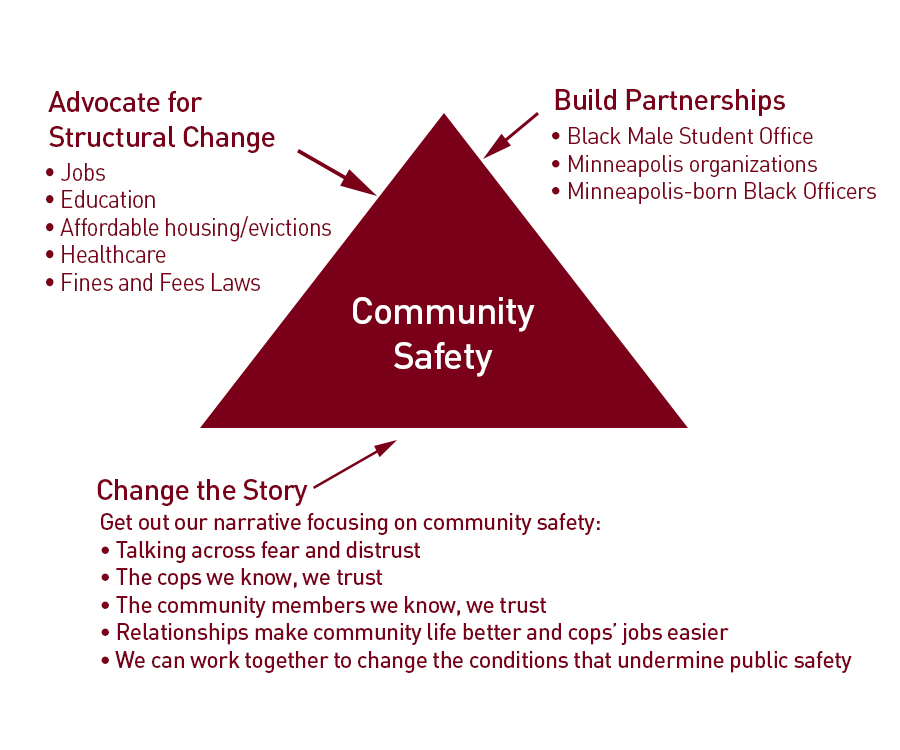

When we turned our focus to what we would do together, it was obvious. We would work on three levels:

- Community conversations to listen, to share our narrative and our story of what’s possible for Police and Black men to do together, and to invite community members to connect with our work

- Involvement in police training so that we could influence the next generation of officers.

- Advocacy for systemic change, with an initial focus on safe, affordable housing.

We began the community conversations after developing desired outcomes and a plan. The initial gatherings, which included a class students at Henry High (through the Minneapolis Schools Office of Male Male Student Achievement), and men in the FATHER Project in Minneapolis, were rich and powerful. When we asked these groups to share with us, they talked about their fears and mistrust of the Police, and then when asked to envision of safe community, they spontaneously came up with the elements of our narrative of Shared Partnership for Community Safety. We knew we were onto something.

Our final step before going public was a meeting Police Chief Arradondo who thoroughly embraced our mission and plan. He gave us the go ahead to be involved in police training and embraced our idea of the Police Department advocating for safe housing as public safety issue. He subsequently began that public advocacy.

Shortly before the pandemic shut down and George Floyd incident, we did our first training workshop with a class of cadets. Unfortunately, our engagement with training and community conversations lost traction during the public turmoil and changes in police department leadership. We also lost members of our group to job changes and relocations. However, we have continued to meet and look for opportunities to re-engage with action steps to further our mission.

Afterword – from Bill Doherty

This story of our work together sounds more coherent looking back than it felt going through it. Most of us wondered at times whether we would hold together. The jury is still out about what difference we will make in our community, and if other communities will want to take the same path of doing deep before taking action. We don’t know if we’ll be able to climb the mountain to its peak, but we do think we’re climbing the right mountain towards the goal of community safety for all.

What we Do

Community Conversations

We do two-hour conversations in schools, social service agencies, churches, and other setting. These involve active listening, honest responses, telling stories (personal and collective), sharing our vision for deeper partnerships, and inviting more connection.

Here’s an example

We had a powerful community conversation with African American students enrolled in a Patrick Henry High School class offered through the Minneapolis School District’s Office of Black Male Achievement. After introductions, we invited these young men to speak at length – with us just listening – on this question: “What’s on your heart and mind about the relationship between the Police and your community?”

Then members of our group, including Police officers, acknowledged what they heard and responded with their perspectives without teaching, explaining, or defensiveness. Just personal and real. The students then began to ask curious questions of the white officers. We then moved into small groups to talk about what a safe community would be like. The young men craved to be heard, and they were prepared to talk about how we move forward to create safe communities. As more than one young man said, “It started here today with this conversation where we were listened to.”

Police Training

On November 7, 2019 we launched the police training part of our work with a two-hour workshop for cadets. It was successful beyond our expectations, with exceptional evaluations from the cadets. Below is the handout we used and the questions we discussed with the cadets in small groups. In 2020 we will expend our training work with new cohorts and will stay involved with the cadets after they begin their police work.

Our mission: We are a group of Minneapolis police officers and black community members building relationships of trust to promote community safety.

What we do: Community conversations, police training, and advocacy for programs and policies that promote safe communities.

Our central messages:

- Distrust of police comes from a long history of police being used by people in power to enforce an unjust status quo.

- Policing in America had its origins in slave patrols, followed by a long history of enforcing Jim Crow laws and other unjust policies.

- We all have a common goal of community safety.

- We can’t police our way to community safety without addressing underlying issues such as poverty and lack of housing.

- The current conversation on community safety is not working: one side points the finger at the police and the other side points the finger at the community.

- We are calling for a Shared Partnership for Community Safety, which involves closer police/community relationships and joint work for systemic change in areas such as housing.

Conversation questions:

- What are the sources of distrust between Police and the black community?

- What would a safe community look and feel like?

- How can we build a safe community together—both in terms of police interactions with community members and larger systemic change?

Community members are Guy Bowling, Brantley Johnson, Justin Terrell, Michael Walker, Damian Winfield, and Corey Yeager. Police members are Charlie Adams, Jon Edwards, Dave O’Connor, Steve Sporny, and George Warzinik. The process facilitator is Bill Doherty of the University of Minnesota.

Safe Housing

We are working to increase awareness of the role of safe, secure housing in community safety.

What we BELIEVE

Our Narrative: Short Version

THE POLICE AND BLACK MEN PROJECT

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Goal: to forge connections between police officers and African American men that can lead to better partnerships for community safety and law enforcement.

Description

- The project evolved out of conversations after high-profile police shootings of Black men in 2015-16. It involves five Minneapolis police officers (three White and two Black) and six Black men from the community. The group is facilitated by Bill Doherty of the University of Minnesota.

- The Minneapolis Police Department approved the project. All group members come as individuals speaking for themselves and not as representatives of an organization. Beginning in January 2017, they agreed to meet every other week fora year or more to build relationships based on honest communication, and then decide on action steps. Meeting places alternate between a community setting and a police setting.

- The first set of meetings focused on relationship building: storytelling to understand one another’s backgrounds and experiences. Over time the group got into more and more difficult conversation including negative personal experiences, the history of policing in Black communities, sources of current mistrust, and different perspectives on recent police-involved shootings. The group kept returning to the table, forming close personal bonds, coming to understand each other’s perspectives, and evolving a common vision for change.

- The group then turned to crafting public narrative statement. The narrative consists of: 1) an analysis of the problem of police and community distrust, 2) an articulation of what we value and believe in common, 3) a common vision for the future, and 4) specific ways we will work together for change. A key focus is on creating partnerships for community safety.

- After meeting outside of public visibility, the group launched its action phase in September 2018 after receiving support from the Chief.

- Action steps thus far have focused on community conversations and advocating for better housing as a public safety issue. A next step is involvement in police training.

Participants: Community group members are Guy Bowling, Brantley Johnson, Justin Terrell, Michael Walker, Damian Winfield, and Corey Yeager. Police members are Charlie Adams, Jon Edwards, Dave O’Connor, Steve Sporny, and George Warzinik. The process facilitator is Bill Doherty (bdoherty@umn.edu) of the University of Minnesota.

Police and Black Men Project Narrative

In 2017, a group of Black Men and Minneapolis Police Officers came together to discuss the issue of distrust between Black men and the Police. Over the course of a year, we came to the following shared understanding and beliefs on how we see the problem and the solutions. Community group members were Joseph Anderson, Guy Bowling, Brantley Johnson, Justin Terrell, Michael Walker, Damian Winfield, and Corey Yeager. Police members were Charlie Adams, Jon Edwards, Dave O’Connor, Steve Sporny, and George Warzinik. The process facilitator was Bill Doherty of the University of Minnesota.

Everyone word of this document was generated, debated, and agreed upon by the whole group.

Narrative Outline

1. The Origin Story – How a table of black men and police officers came together to talk about distrust between our communities and ended up talking about how to build safe communities.

2. How we see the Problem – Why there is distrust between Black Men and Police Officers

3. Core Beliefs – What we believe

4. Imagine a Safe Community – Our aspirational vision for safe communities

5. Our Theory of Change

1. Origin story

The project came out of a conversation between Bill Doherty, of the University of Minnesota’s Citizen Professional Center, and Guy Bowling, director of the FATHER Project in Minneapolis. Bill (a White man) and Guy (a Black man) had worked together on community projects for many years. Their conversation occurred when the community was reeling from the death of Philando Castile after a traffic stop by a police officer in Falcon Heights. Guy posed the question about whether Bill’s Families and Democracy model could be applied to the problems between Minneapolis police and Black men. This approach focuses on grass roots relationship building prior to action steps, rather than traditional top-down programming.

The basic idea that emerged was that a small group of police officers and Black men from the Minneapolis community would meet frequently over at least a year to develop relationships of trust and then decide on joint action steps.

Bill and Guy knew they could personally recruit the Black men from the community, but neither had ties to the Minneapolis Police Department. So Bill consulted with a well-connected friend who suggested starting by running the idea past Bob Kroll, head of the police union. Bill sent Bob Kroll an email in January 2016 and immediately received a positive response and an invitation to meet Officer Dave O’Connor, a union leader and public engagement officer. That month Bill met over coffee with Dave and his partner, who were enthusiastic. Dave then discussed the idea with his colleagues and superiors, and got green lights. Finally, Bill contacted the Chief Harteau who met with him along with her Community Liaison Sherman Patterson. The Chief approved the idea with great interest, and entrusted Sherman Patterson with setting up a process of selecting the officers.

The group to be recruited would consist of five officers (one Black, five White) and seven Black men from the community. (one White officer subsequently dropped out and was replaced by another Black officer.) Officers were nominated by a group consisting of Deputy Chief Arradondo, Sherman Patterson, Dave O’Connor and Bill Doherty (Bill had final screening authority). Once a group was nominated, we met with the Precinct Inspectors to get their buy in and willingness to approach the nominated officers. The Inspectors were uniformly positive about the project and then recruited their officers. The community members were nominated by Guy Bowling and Bill Doherty (one was nominated by Sherman Patterson), and interviewed by different combinations of Bill, Guy, and Sherman.

The group began its biweekly meetings in January, 2017, with this goal: to forge connections between police officers and African American men that can lead to better partnerships for community safety and law enforcement. With Bill facilitating, we used a process of building relationships through personal storytelling, then opening up challenging topics, and deciding to create a common narrative to describe who we are, how we see the problem, what we envision for a safe community, and how we act together to bring about change.

2. Why is there Distrust between Black Men and Police Officers?

There is a history of Police being used to enforce and protect an unjust status quo.

This history goes back to slavery, slave patrols, and Jim Crow. We see it continuing today with inconsistencies in the criminal justice system and with laws and policies that have led to mass incarceration. Historically, Black people have been seen as threats to be controlled, with Police being one of many mechanisms of control and protection for the powerful. These traditions have developed a culture that produces lifelong distrust between us.

Police and Black men lack a shared understanding and relationship with each other.

Without a relationship between the two groups, we both become the “Other” who is seen as a threat. We ignore the innate values and beliefs we share in common, including the value of safe communities. Therefore, the only way to build trust is by moving into relationship with each other to tackle the issues that undermine community safety.

There are underlying issues (poverty, family instability, housing, education, health care, and others) that undermine the ability to build relationships for community safety.

Simply inserting Police officers into stressed, resource-challenged community without addressing underlying problems sets up both groups for bitter, fractured relationships, and makes safety harder to achieve.

There are common, dehumanizing, media-driven stories about each of us (both Police and Black men)—that we are violent, guilty, suspicious, uneducated, and have broken families.

These stereotypes dehumanize us and pit us against each other, undermining trust and the ability to work together on common goals.

3. Our Core Beliefs

As a Community of Black Men and Police Officers, we believe:

- That we have a common goal of community safety.

No one wants to live in fear and everyone wants the best for their loved ones. Our common goal of community safety is based on wanting to feel safe and secure in our homes, neighborhoods, work places, and the communities we visit. This shared goal of community safety drives everything we want to do together.

- That we can’t police our way out of the problem of lack of community safety.

Police by themselves cannot create safe communities. Rather, ordinary people do–family members, neighbors, co-workers, classmates, and community leaders. Trust and a sense of connection between people are what make communities safe, and these require resources that are often lacking. By the time people call the police, community safety and trust are already threatened or violated.

- That ongoing police training, while necessary, is not the solution.

A well-trained police force is essential, but focusing on training is too limited a response to the challenges facing community safety. Our local governments and civic leaders must invest resources in communities in a way that fosters more trust, connection, and economic stability. People feel safe and avoid crime when they can work, find good housing, educate their children, and feed themselves and their families. Investments in training police officers should be framed as one part of a much larger solution, and not just as a visible response to social pressure.

- That we each catch the blame for lack of community safety, and that we have to get closer together to address the problem and make a difference.

As mentioned, Black men and Police are feared and stereotyped. Black men are seen as dangerous and a threat to be controlled. Police are seen as dangerous and as a force to control people. There is immense power for change if both sides could bust these stereotypes and work together for community safety.

- That people in power (those who make decisions and have lobbyists) think they know best and share no blame for the problems facing us and the community.

They are held to a different standard and often tell distorted stories about us through the media. They are disconnected from both the Police and the Black community, and they derive benefits from the current situation. We want to build relationships with people in power, so that they can know us and we can know them, for the sake of joint solutions.

4. Imagining a Safe Community

We imagine a safe community:

- Where people are in relationship with each other and connected through a sense of community

- Where people watch out for one another

- Where the neighborhoods are safe and clean for kids and families

- Where bad things still happen but justice is restorative and healing, and not just focused on punishment

We imagine a safe community where policing is:

- Truly community based: they are your family, friends, and neighbors, and what happens to the community impacts them

- A profession that is trusted and honored by the community, and

- Officers aren’t feared but seen as resources

We imagine a safe community where Black men:

- Are free to be themselves and accepted for who they are

- Have no barriers to their success – they have housing, employment and the resources to address basic needs and social aspirations

- Can go anywhere without fear

- Feel an ownership of their lives, their families, and their communities

We imagine a safe community where the wealthy and powerful:

- Feel a stake in the success of people with less wealth and power

- Personally know people in the community

- Use their wealth and power so that others can have wealth and power

5. Solutions and Theory of Change

Two Common Narratives and Our Alternative One

The current public debate focuses on two competing narratives, one focusing only on police accountability and the other focusing only on personal responsibility. Although each narrative has valid points, both are limited and keep us stuck in finger pointing. We are offering something broader and bolder: a narrative of partners for community safety.

Police Accountability Only

This narrative argues that a set of policy changes that can hold Police accountable to a high enough standard that will prevent Police misconduct.

Examples

Oversight boards, body cameras, changes to policies and procedures, and ongoing bias training.

Personal Responsibility Only

This narrative argues that Black men and the community need to bear the responsibility for crime and thereby avoid Police use of force.

Examples

Call for “law and order” and cooperation with Police. Accusing the community of not emphasizing civilian violence in the same way it responds to state violence.

Partners for Community Safety

This narrative focuses on a shared goal of community safety. All people want to feel safe and free. Rather than focusing on punishment, the community and any state agent who engages with the community is focused on the overall goal of safety.

Examples: Officers who live, work and play in the community, and who are in proximity to the community and foster mutually respectful relationships. The Police Department and community partners work together to promote the necessary conditions for safe communities, including better housing, jobs, education, and health care. These changes benefit everyone – community and Police alike – because Police are part of the community and we all want safe lives for ourselves and our families.

Limitations of the Police Accountability as the Main Narrative: It’s not collaborative, often adversarial, leads to specific policy shifts rather than major cultural changes, does not address the larger forces that create unsafe communities — and many communities are still unsafe even if Police change.

Limitations of the Personal Accountability as the Main Narrative: Fails to recognize the larger forces that create unsafe communities, and doesn’t invite Police changes.

Advantages of the Partners for Community Safety Narrative: Police and Black men are allies to help the community become safe, developing closer relationships so that Black men feel safer with Police, Officers’ jobs are easier, and working together could lead to systemic changes needed for safe communities.

WHO We Are

Community Group Member Participants

"I am a community member, Director of the FATHER Project, and a father/grandfather. I helped found this project because I envision a community that’s safe, collaborative, unified, and works together to solve community problems/issues. I contribute expertise on fatherhood and black males and on the Families and Democracy Model."

Guy Bowling

"I am a community member, a community leader, and mentor. I am a father and have lived on the North Side for 20+ years. I’m in this project because I want to make a difference for my community. I contribute my group process skills to the project and my vision about what can happen when groups with historic differences come together to solve problems neither side can solve alone."

Brantley Johnson

"I have a background as an organizer and I am currently Executive Director of the Council for Minnesotans of African Heritage. I live with my wife and two sons. I joined this project because I believe change is possible. Change happens when people come together and demand that things change. I am dedicated to having consensus conversations with anyone who can help being about community-driven realization of safety. I contribute a community base, policy experience, and a powerful story of why we need to address these issues."

Justin Terrell

"I’ve been a member of the FATHER Project for more than 14 years, and a Citizen Father for 9 years. I am a father of seven kids and a grandfather of five. I am a security guard/bouncer, an adult foster care crisis aide, and I own a window cleaning business. I joined this project because I believe that working on the community together starts with working together in the community. Pride can be re-energized in a community a shared task of work. I bring to the project transparency and a voice for the streets. I bring heart and balance."

Damian Winfield

"I am a marriage and family therapist, a dad, an activist and life coach. Being a part of the Police and Black Men Project since its inception affords me an opportunity to address long held ills that impact the Black community. I believe deeply that to address systemic struggles, we must begin with creating and nurturing relationships. This Project does just that."

Corey Yeager

"I am Executive Director of C.E.O Change Equals Opportunity, a life skill’s mentoring program for youth ages 12-27 with focus on exposure to college, career, and cultural experiences and opportunities. I am Co-founder and Commander of the Minnesota Freedom Fighters, Head Basketball Coach at Patrick Henry HS, Teacher within MPS with the Office of Black Student Achievement, Consultant for the City of Minneapolis with focus on youth violence prevention. I joined this group to continue to foster a healthy relationship with community and police to hold each accountable for the health and wellness of the youth we serve."

Jamil Jackson

"I’m a Minneapolis Northsider who spent 20 years as a Minneapolis Police Officer. I’m a Football Coach who continues to mentor young men in The North Community. I’m Director of Team Security for the Minnesota Twins. I’m a husband and father with 3 adult Children. I’m the son of a 35-year Black Police Officer who continues to mentor in this community. I’m a product of so many good things in North Minneapolis and continue to grow. I’m part of this group to follow the leadership of the great ones before me."

Charles "OA" Adams

""

Ezra Hyland

""

Prince Corbett

""

Todd Kurth

Police Member Participants

"I’ve been a Minneapolis Police Officer for 35 years. I currently am a Commander in the Police Recruitment and Backgrounds Division. I’m a father of three, and all of my children are adults. I was asked to be part of the project because of my dual roles as a police officer and being a black man. I contribute to the project with my community background and being a proud member of North Minneapolis."

Charlie Adams

""

Rich Hand

"I am a Police officer with 13 years in the department. I’m a part of this project to learn and build relationships and to understand and teach our own group members and the community. I bring to the project a hope that better understanding and relationships can lead to collaboration and stop the US vs THEM mentality. I know that we are all human: we hurt, we bleed, we love, we cry, and we have difficult struggles (babies dying, kids hurt), and we cope the best we can, as any human can."

Steve Sporny

""

Sam Erickson

"I’ve been a police officer since 2007, working out of the 4th Precinct (North Minneapolis). I am married with two children. I joined this project because of the need to bridge the gap between police officers and the community after two high profile officer-involved deaths. I contribute a voice for the police patrolman who works in a challenging urban setting."

George Warzinik

""

Pete Stanton

"I fulfilled my childhood dream of becoming a Minneapolis Police officer in 2006 after being in the active-duty Air force for 7 years. Putting on this uniform in the same zip code I grew up in was important to me because the community that supported me growing up and getting my education at North High, needed my support in return, and I felt an obligation to do so. I joined this group because it has become more important than ever to break down barriers and find true leaders in the community to collaborate with true leaders in the MPD and use those joint forces to make an impact through many avenues. Being a part of a group that is willing and able to have tough conversations, ask tough questions, and be accepting of others view points and feelings is the ultimate experience for me!"

Will Gregory

Process Facilitator

"I am a University of Minnesota faculty member, a family therapist, and the process leader on the project. I am a husband, father and grandfather. I’m in this project because the only way to bridge the historic divide between the Police and the Black community is to forge honest relationships and work in partnership to create community safety. I contribute to the project through my group process skills and my commitment to holding groups together for difficult conversations and collective action."

Bill Doherty